Dragon and Haroldus were deep in conversation as Jane approached. They were at the far end of Rake’s garden, and it sounded like Dragon was explaining his bowel movements in rather more detail than court society was accustomed to.

‘Twice a day,’ said Dragon. ‘three if garden boy is lucky and turnips are involved. Turnips, very woody, so most of it passes right on through.’ This end of the garden contained Rake’s pride and joy, his compost heap. It was a massive pile, two stories high, consisting of dragon dung, horse manure, kitchen waste and all the weeds and clipping from Rake’s daily maintenance of the castle grounds.

‘So, you really do only eat vegetables?’ Haroldus was making notes in his journal.

‘And fruit. Love my fruit.’

‘No meat at all?’

‘Not meaty meat. Bug meat. Little grassy eating hoppy, hoppy grubs can be innocent casualties.’

‘Not forgetting the worms, weevils, caterpillars, fruit flies, ticks and tapeworms.’ Jane sat down on one of Dragon’s front paws and gestured to the dung pile beside them. ‘This gong heap is the secret to Rake’s gardening skills, two spadefuls and he can grew anything.’

‘Except bananas,’ sighed Dragon. ‘That boy’s a disappointment when it comes to bananas.’

‘Agreed. ALMOST anything,’ said Jane. ‘I am forever urging my father to sell this gong by the barrowload.’

‘Top up the castle coffers?’ Haroldus laughed. ‘Your father is the King’s chamberlain, is he not?’

‘Chamberlain, chancellor and royal whipping post.’

‘So I hear,’ laughed Haroldus. ‘Anyone who has to manage a King’s purse must except that. There is a proverb - The strings of the purse are a sting and a curse. But you are right about the value of gong, Jane. It is prized the world over. I have been to a kingdom where caves were fought over for their precious content. Bat Gong!’

‘Disgusting,’ Jane pointed up the steps leading up to the Royal Gardens above. ‘Do you see that tower?’ From where they sat it was impossible to see the gardens themselves, just the tops of the trees and the battlements of one corner tower.

‘I do.’

‘A few short weeks ago that tower was full of bats. Jester and I helped Pepper to clean it. The King has forgiven the herbalist who used to live there, the man will be returning soon.’

‘You mean the old magician he expelled? Theodore spoke of him once. A very learned man by all accounts.’

The king gave him the title of magician, the man himself never used it. Any talk of spells and magic potions annoyed him, his skills were healing fevers and ailments.’

‘Magic is for storybooks,’ said Dragon.

‘So speaks a giant green dragon. Many would declare you to have arrived in this world from some spell.’

‘From an egg,’ said Dragon, nodding to himself as if confirming the wisdom of his own words. ‘No spell. It’s eggs, all the way down.’

‘We are drifting from the points,’ said Jane. ‘I was remarking on the terrible smell we had to endure from the bat gong.’

‘And yet no smell from this compost,’ Haroldus grinned up at Dragon. ‘How very fortunate for everyone. Perhaps it is the lack of meat. The horses eat grass, and you eat vegetables. This really is most fascinating, and none of it is in the ancient literature. Dragons were persecuted for centuries, blamed for stealing livestock.’

‘Yes,’ Jane smiled up and Dragon, ‘I blame this one for a great many things, but not for eating sheep.’

‘So much information has been lost,’ said Haroldus.

‘Not for long,’ Dragon reached down and patted Jane’s red hair with the tip of one claw. ‘This little flame-head has pledged her life to discovering everything there is to know about dragons.’

‘Is that true?’ Haroldus but down his quill and stared at Jane. ‘How can such a pledge be made? You have made a pledge to serve your King have you not?’

‘I have,’ Jane got to her feet and stretched. ‘So far the two pledges sit together well enough.’ She reached up for Dragon’s knee and in three swift moves had swung herself up onto his neck.

‘And when they don’t?’ Haroldus craned his neck to watch Jane settle in behind Dragon’s head and grasp his horns.

‘Then we shall see,’ said Jane. She squeezed gently with her knees, a signal to Dragon that she was ready. Dragon leapt over Haroldus, bounded up the wide steps that led to the Royal Gardens, and launched himself into the sky. Haroldus watched them, shaking his head in a mix of wonder and disbelief. The great age of dragons had long passed. That was the common wisdom. There had been many sighting over the years, tales from around the world of just one green dragon; an elusive beast who kept to mountain peaks and remote islands. This dragon? It was hard to reconcile this talkative beast with the image of a reclusive dragon who shunned civilization.

Yet here he was, and with a young woman riding his back like an Attendant of old. Did this poor child understand the true nature of her pledge? Haroldus shook his head. No, of course she didn’t, or she would never have sworn her knight’s oath to the king.

‘What was all that fiddle, fuddle talk?’ shouted Dragon. They were flying up to his cave. A direct flight would have meant a steep angle, too hard and too dangerous with Jane on his back. Instead he circled the mountain in a steady upward curve.

‘Who knows,’ said Jane. She had no need to shout, Dragon’s ears were close to the temple horns she was holding. By dipping her head to the right or left she could whisper directly into either ear.

‘He knows something we don’t,’ shouted Dragon. ‘You said he was a learned scholar. We should question him?’

‘I will, tonight. Sir Theodore has asked me to join them for supper in the tavern.’

‘Good, and if he refuses to talk, we bring him here and I will question him, dragon style.’

‘No.’

‘Not your decision.’

‘It is if you want me to keep helping you. My duty is to protect and serve the kingdom, that includes protecting everyone from you as well. If you harm a shortlife, the King will have you driven from these mountains.’

‘So, it wasn’t just fiddle fuddle talk. Haroldus was right. One day you must make a choice. You keep your promise to me, or you keep your promise to your King.’

‘No, everything works perfectly just the way it is. You help me with my duties. I help you discover the history of dragons. We will work it out; we always do. Unless YOU break your pledge to me.’

‘Never.’

‘Good, because hurting Haroldus would not be helping me in my duties, would it?’

‘Fiddle fuddle!’ snorted Dragon.

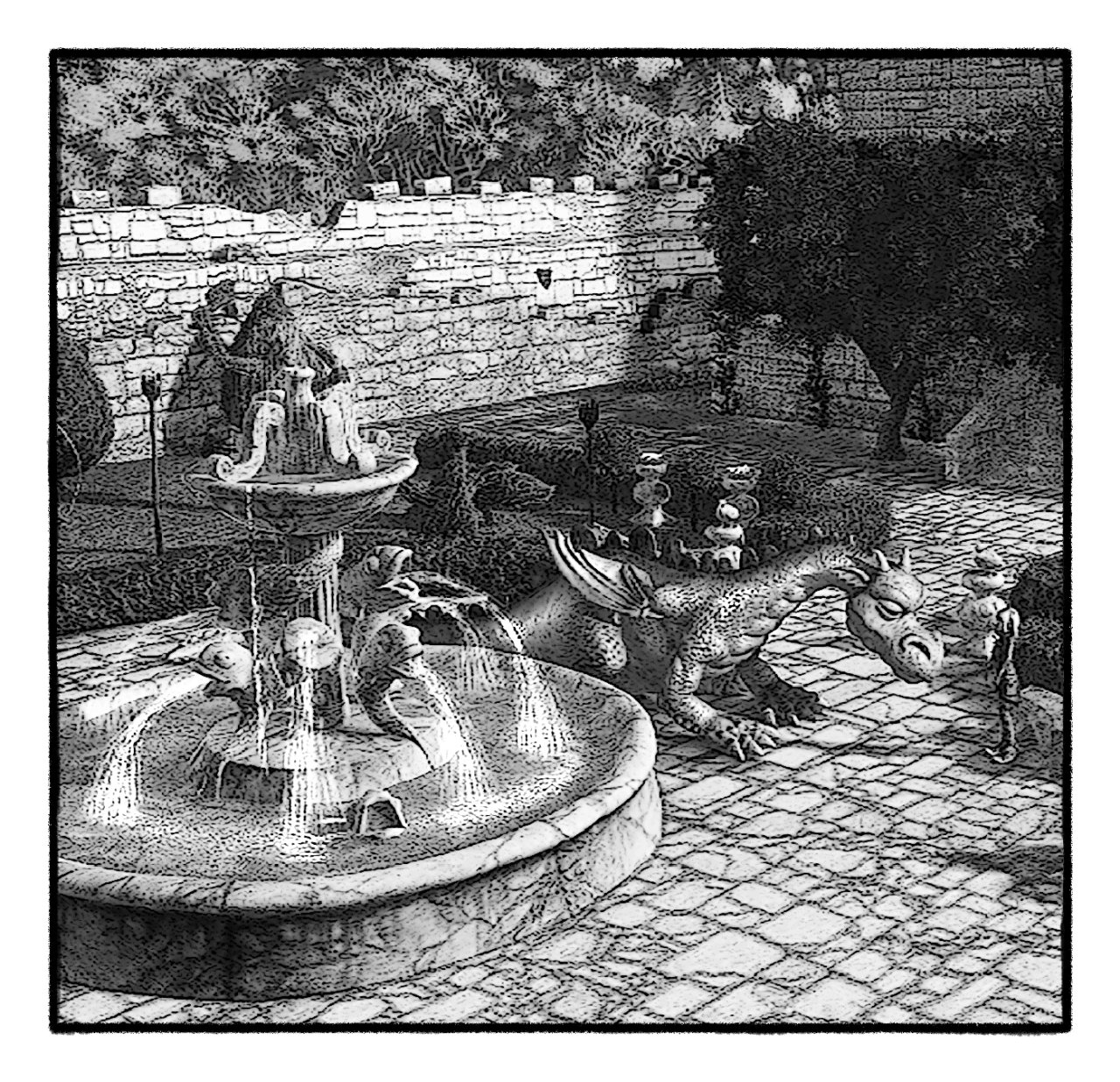

They landed on a wide ledge that poked like a tongue from the mouth of the cave. Jane jumped down and followed him inside. The entrance opened into a wide cavern, its walls covered in scratched dragon runes. It was the start of a labyrinth of caves that burrowed deep into the mountain. Jane had spent much of her free time exploring the tunnels and passageways.

‘To your junk pile?’ she asked.

‘To my treasure, yes.’

Jane pulled a torch from a bracket on the wall, dipped the end into a bucket of pitch and held it out for Dragon. He whispered a tiny curl of flame and ignited the torch.

Dragon’s sleeping cave was a short walk from the first cavern, and it was treasure trove of found items. Dragon had been hoarding for centuries, collecting anything with dragon runes carved on it.

‘Anything in particular you want to study?’ Jane held the torch up, sending its flickering light across the massive heap of objects.

‘Yes! This.’ Dragon reached into the pile and pulled out a small bronze statue. He set it on the ground between them, then lay on his belly to look at it, his head cradled in his front paws. Jane settled down beside him.

Runes were carved in a single line all around the base of the statue. Most of the runes were a mystery, but among them were a few Jane and Dragon had deciphered over the years. Two appeared more than once. The rune for DUTY and the rune for LOVE.

The statue had seen better days. It was ancient, the bronze work black and pitted, but the depiction was still clear. It showed a dragon’s egg splitting open, the sharp claws of an infant dragon protruding from the crack.

The noise in the tavern made normal conversation a challenge. Everyone had to raise their voices to be heard, even to friends at their own table. Sir Ivon was sharing a joke, and everyone was listening hard for the punchline. When it came, they pretended to understand. Sir Ivon’s thick accent could be hard to follow, even outside on a quiet day. Here in the tavern, his voice lubricated by a tankard of ale, it was challenging.

Sir Theodore had secured a corner nook, which gave the party some sense of seclusion. The table was long and narrow, a single seat at the head for Sir Theodore with benches on either side. On one sat Sir Ivan and Haroldus, across from them sat Jane, flanked by Smithy and Jester.

The main floor of the tavern was a riot of noise and colour. Every table was crowded, mostly with locals; farmers who had come to trade in the town square; fisherman waiting for the night tide, plus barrow boys, wainwrights and salters from the packing sheds.

Jane knew them all, their names, their faces, their strengths, and their weaknesses. Her duty was to the King, and these were his subjects, so her duty, by extension, was also to them.

‘Think of them as my children,’ the King had said to her once, shortly after her pledging ceremony. ‘They stray at times; they have their tantrums; indeed they might one day challenge their father. But they are my family Jane, they are under my protection. And so, by virtue of your new position, under yours too. You are the eyes and ears that must watch over them.’

She watched them now as she listened to Haroldus matching Ivon joke for joke. There were always some strangers in the town, faces she didn’t recognize, traders from visiting ships. Seated at one table were the boat crew working for Haroldus, at another, foresters from a woodland kingdom two days ride to the north. They were large men with broad backs and strong arms, down from their mountain homes to sell timber and resin to the boat yards.

‘Roudy lot. All fueled up on ale,’ said Smithy. Jane didn’t reply, she had registered them when they first came in. Most foresters were famous for bouts of heavy drinking and picking a fight simply for the sport of it. One of the men had spent the best part of his meal staring at Jane. He was taller than the others with black hair tied in a long ponytail down his back. The man raised his mug of ale to Jane, then raised one eyebrow. Jane stared back. He smiled, Jane didn’t. One of his colleagues watched the exchange, took the man’s face in both hands, and turned it from Jane, slapping him hard on one cheek. The man laughed, put down his ale, and approached Jane’s table.

‘Good evening, friends. Would you be so good as to settle a wager I’m having with my team.’ He glanced at each face in turn, then settled his eyes on Jane. ‘It concerns the number of freckles on the sunny cheeks of yourself, lass.’ Jane said nothing. She sat back, held the man’s gaze, and raised an eyebrow. No-one else moved.

‘I’ll need to take a closer look,’ the forester gestured back to his table where his friends were watching the encounter. ‘From over there I counted fifty at the very least.’

Across the table from Jane, Haroldus glared at the forester before turning to Sir Theodore. ‘Are you going to stand for this?’

‘No indeed, I shall remain seated for it,’ Sir Theodore reached for his mug of ale and winked at Jane over the rim as he took a long draught.

‘Aye,’ Sir Ivon nodded, and raised his own glass. ‘Sit this one out Haroldus. Very shortly you’ll be wanting to make a wager of your own.’ The forester ignored them; his attention fixed on Jane. He leant in and raised his voice, clearly wanting the whole tavern to hear.

‘Given the amount I’ve wagered on the precise number of your freckles, I would ask you to step out from the shadows of this corner table, and join me by the fire where I can take a closer look and verify the count.’

‘Goodness,’ said Jane. ‘You are reckless. Risking humiliation in front of your friends on account of a few freckles?’

‘Account?’ The man frowned, then understood the play of words. His smile grew wider. ‘Freckles and brains! Wonderful. But no, there will be no humiliation for me tonight. You will join me by the fire, my colleagues will applaud me, and I will count your freckles as you tell me how you came by them. Hard won, no doubt, one for every kiss you have provoked.’

Oh, I smell the poetry of romance,’ said Jester. ‘This fellow is quite the orator, Jane, we must allow him that. Too much time alone with his axe, no doubt. I wonder if it has a name, Betty The Blade, perhaps?’

‘You could ask her yourself,’ said the man, ‘She’s right outside, asleep on the wagon. I can introduce you right now, but take care as she has a sharp tongue.’

‘I like this man,’ Jester slapped the table. ‘Jane, please go easy on the poor fellow.’ Jane nodded and gifted the forester with a smile.

‘You are correct, neighbor, my freckles have all been hard won from a great many kisses. One for every skull my stave has kissed. Shall I earn myself another, here and now, in front of your friends?’

‘Staves? With you?’ The man laughed and shook his head.

‘Yes, right here, right now.’ Jane stood up and took a step, forcing the man to step backwards. ‘Last chance, friend. Return to your table now, unmarked, or be carried from the tavern with a fresh dimple on your pretty face. The choice is yours.’

‘I would never be so ungracious as to fight a young lady.’

‘Lady!’ Jane glared up at him, her eyes level with his throat. ‘I will not be so insulted. Do I look like a lady?’ She pushed passed him and clapped her hands to the tavern owner, a stout man Jane had known all her life. ‘Master Brewman, this customer has refused my offer of staves. What say you to that?’

‘I say he is a very wise man, Jane Turnkey. Clearly word of your skills has reached his ear. However, in the event that he is NOT a wise man, I shall fetch your staves.’

‘How intriguing,’ the forester took a few steps towards Jane, his smile wider than ever, his dark eyes shining. ‘In all my years nobody has ever accused me of being wise.’

‘We’ll vouch for that!’ roared one of his friends. Then Smithy began thumping the tabletop in front of him with his fist. Jester joined in, and so did other locals around the tavern, a slow pounding beat as they started to chant: ‘STAVES …STAVES …STAVES.’

‘What is this?’ laughed the forester, as the men at his own table joined the chorus, thumping and chanting along with the locals.

‘Here you go!’ Master Brewman appeared from the back room with two staves, he threw them to Jane who caught them both, one in each hand.

‘Do you have a name?’ she asked, tossing one of the staves to the forester. ‘I like to know the owner of every skull I crack?’

‘It’s Robert,’ the man started spinning the stave, tossing it from hand to hand before twirling it in a series of complex arcs. ‘Young lady, before we go any further, you are aware that I heft an axe every day for my bread.’

‘You would be a poor forester if you didn’t. But can you dance?’ Jane rapped the floor with the heel of her stave. ‘Dance floor please.’

‘Dance floor?’ Robert watched as locals jumped up and dragged tables aside, clearing the center of the tavern. Two tables remained, set a few yards apart. Master Brewman arrived carrying one end of a long plank, his wife carrying the other. They set it between the two tables to form a narrow bridge.

‘This dance floor,’ said Jane. She leaped onto one of the tables and gestured for her opponent to take the other. ‘That is your castle. Defend it well. If you fall, you lose. If I take your table, you lose.’

‘And if I win?’

‘You may count my freckles in the firelight. And if I win, you pay for my evening meal and that of my friends.’

‘Then prepare your cheeks for the counting.’ Robert jumped onto his table and grinned over at his friends. ‘And you, traitorous lot, stop your chanting and prepare to leave town without me. So many beautiful freckles will take a whole night to count.’

With that, Robert twirled his stave and stepped out onto the plank. Jane watched for a moment; her own stave held loosely in her left hand. Why did so many men parade their self-assurance in this way. Gunther was the same, always making a big display of any new skill he acquired, as if it would intimidate Jane, when in truth it gave her an advantage, a moment to analyze her opponent’s stance.

She used that moment now, watching Robert as he stepped forward with his right foot, his stave in both hands, his left at the center, taking the point of balance, his right doing all the work. So the man would favor striking down from his right shoulder.

Jane watched a moment longer, tracing each arc of the twirling stave, counting them like the swish of a skipping rope. One and two and… She raced across the plank in three steps and tapped Robert lightly on one cheek before he could raise his staff to defend the blow. Jane smiled at the surprise on his face. She could have followed through with the blow and ended the contest right there.

‘Nimble,’ he said. ‘And gracious. You are a parcel of surprises. Was I wise to accept your challenge?’

‘No,’ Jane stepped back, raised her staff to the vertical, spun a full circle, holding the staff out as she span, then dropped to her knees and brought the staff cacking into the meat of the man’s left calf. His leg buckled and fell from the plank. Jane jumped down lightly beside him.

‘Thank you kindly for the entertainment, please settle our bill on your way out.’ The other foresters applauded as they helped Robert to his feet. Jane returned to her friends and the locals dragged their tables back into place.

‘Did you break it?’ asked Jester.

‘His leg? No. His dignity? Certainly.’

‘The man has a living to make,’ said Sir Theodore, ‘perhaps a wife and children to feed. So I applaud the move, Jane. But if this had been a true fight, what then?’

‘I would have struck his shin and snapped it.’ Jane sat down and reached for her mug of spiced milk. She rarely drank ale; it made her head cloudy and troubled her sense of balance. She preferred milk, especially here in the tavern where they warmed it on the fire and added nutmeg and honey.

‘His friends will be retelling the story for months,’ said Smithy.

‘For years,’ laughed Jester. ‘They will celebrate it with a rowdy drinking song. I’ve a mind to write one myself.’

‘Sir Theodore was relying on you, Jane,’ Haroldus slapped his old colleague on the back. ‘He ordered another round of drinks and a plate of sweetmeats as you stepped out there. And given the speed at which the locals set up the tables, it’s clear you make something of a sport out of this.’

‘I take my training where I can,’ said Jane, helping herself to two of the glazed pastries. ‘So tell me Haroldus, you and Dragon where thick as thieves earlier. What were you talking about?’

‘In truth I was mostly listening. I thought it would be hard to make conversation with him, and yet the opposite was the case. Once started, he was like a breached dam. Impossible to stop.’

‘That’s Dragon,’ laughed Smithy, ‘I find him talking to pig some mornings, the poor creature has no idea what Dragon is saying, but she likes the smell of his breath and stays close and attentive, making little grunts of encouragement.’

‘He asked me about dragon runes,’ said Haroldus. ‘He has seen them carved all around the world and has gathered a large collection.’

‘He has,’ Jane’s mouth was full of pastry, she held up a finger, Haroldus waited. Jane swallowed, and continued. ‘There are runes and paintings all over his cave dating back to his birth.’

‘He was hatched here?’

‘Perhaps. He has no memory of it, of course. But there are tales of a young dragon being sighted on the mountain generations ago.’

‘More than tales,’ Sir Theodore reached for a pastry. ‘We have written accounts in the royal library, the sightings happened when the foundations of the castle were being laid.’

‘That is a tale right there,’ Ivon thumped the table, ‘all kinds of shenanigans, masons refusing to work, rock falls, buried treasures.’

‘Treasure?’ Haroldus turned to Sir Theodore. ‘Is that what keeps you here, old friend? What other secrets are you holding from me?’

‘As many as I can,’ the old knight chuckled, but Jane could see it was forced. The twinkle had gone from his eyes.

‘The runes are the treasure.’ Jane brushed pastry crumbs from the front of her tunic. ‘Dragon chooses to believe those early sightings were of him and that the runes where carved by the dragon who laid his egg. He is obsessed with translating them.’

‘Understandable.’

‘He longs to uncover the true history of dragons, not the tales told by shortlives, but their own story, told in their own language. Scraps are everywhere, copied by humans on parchment, but no-one can read them. All the learning has been lost. We’ve translated a few runes, simple ones. But I have promised Dragon we will work together to unravel his whole story in time.’

‘We are fellow explorers then,’ said Haroldus. ‘We chase down life’s mysteries. One of my crew is from the Rust Mountains to west of here, he spoke of a valley there, a spot where a rock fall has revealed a cavern with many carvings.’ Haroldus reached into his pocket and handed a small square of parchment across the table. ‘I haven’t seen them myself, so it may be nothing, but I had the man draw a map if Dragon cares to investigate.’

‘Oh, he will care,’ said Jane. ‘We will take a look.’ She glanced at Sir Theodore. The old knight said nothing, but raised one eyebrow very slightly. That is, when my castle duties allow me the time.’